Code Name Bananas

Themes explored in this book: Friendship, loyalty, family, kindness, courage, bravery, hope, resilience, empathy, imagination

There’s something instantly funny and disarming about a boy, a gorilla, and a Nazi plot all sharing a children’s book, and Code Name Bananas leans right into that combination of chaos and charm. I picked it up because I wanted to understand David Walliams’s style properly, rather than just knowing him as “that very popular children’s author who used to be on the telly”. I ended up enjoying the story a lot—even while feeling, at times, that the fonts were shouting at me from the page.

Set in 1940, the book follows eleven-year-old Eric, who spends as much time as possible at London Zoo. That’s where he visits his favourite animal, Gertrude the gorilla, and where his Uncle Sid works as a keeper. Britain is at war with Nazi Germany, bombs are raining down on London, and the zoo—like everything else—is under threat. When danger comes a little too close to Gertrude, Eric and Sid decide they can’t just stand by. Following a terrible decision by the zoo, they rescue her and go on the run, only to stumble into a larger, secret Nazi scheme that gives the story its madcap, spy-adventure energy.

The emotional centre of the book is Eric. He’s the classic Walliams child hero: slightly odd in the eyes of others, underestimated, and much braver than he thinks. Others describe him as having sticky-out ears and the nickname “Wingnut,” which suggests how people around him treat him.

What I liked about Eric is that he doesn’t start as a hero at all. He’s just a boy who loves animals and wants to be somewhere he feels safe. His courage arrives gradually, wrapped in fear, bad decisions and impulse. That makes his choices towards the end of the book feel more earned than some children’s adventure stories, where the main character is “destined” from the start.

Sid, his maternal great-uncle, brings a different kind of warmth. He’s part comic relief, part emotional anchor. Sid is a grown-up who remembers what it’s like to be a child, which is surprisingly rare in fiction for younger readers. There’s a lovely line where he tells Eric,

“Don’t let the bullies get you down! It’s what’s in here that counts,” said Sid, clutching his heart. “You are a smashing boy – don’t ever forget that!”It’s simple, but it lands. It’s the kind of sentence a younger reader might actually remember in the playground, which feels very in tune with what Walliams is trying to do.

Gertrude the gorilla is pure delight. She’s everything you want from an animal companion in children’s fiction: expressive without speaking, clumsy in a way that drives the plot, and always just slightly out of place in the human world. The book has fun with the logistical absurdity of smuggling a gorilla out of London and passing her off in public. As other reviewers point out, this is not especially realistic historical fiction—no one is reading Code Name Bananas for strict wartime accuracy—but the historical setting gives the silliness some weight.

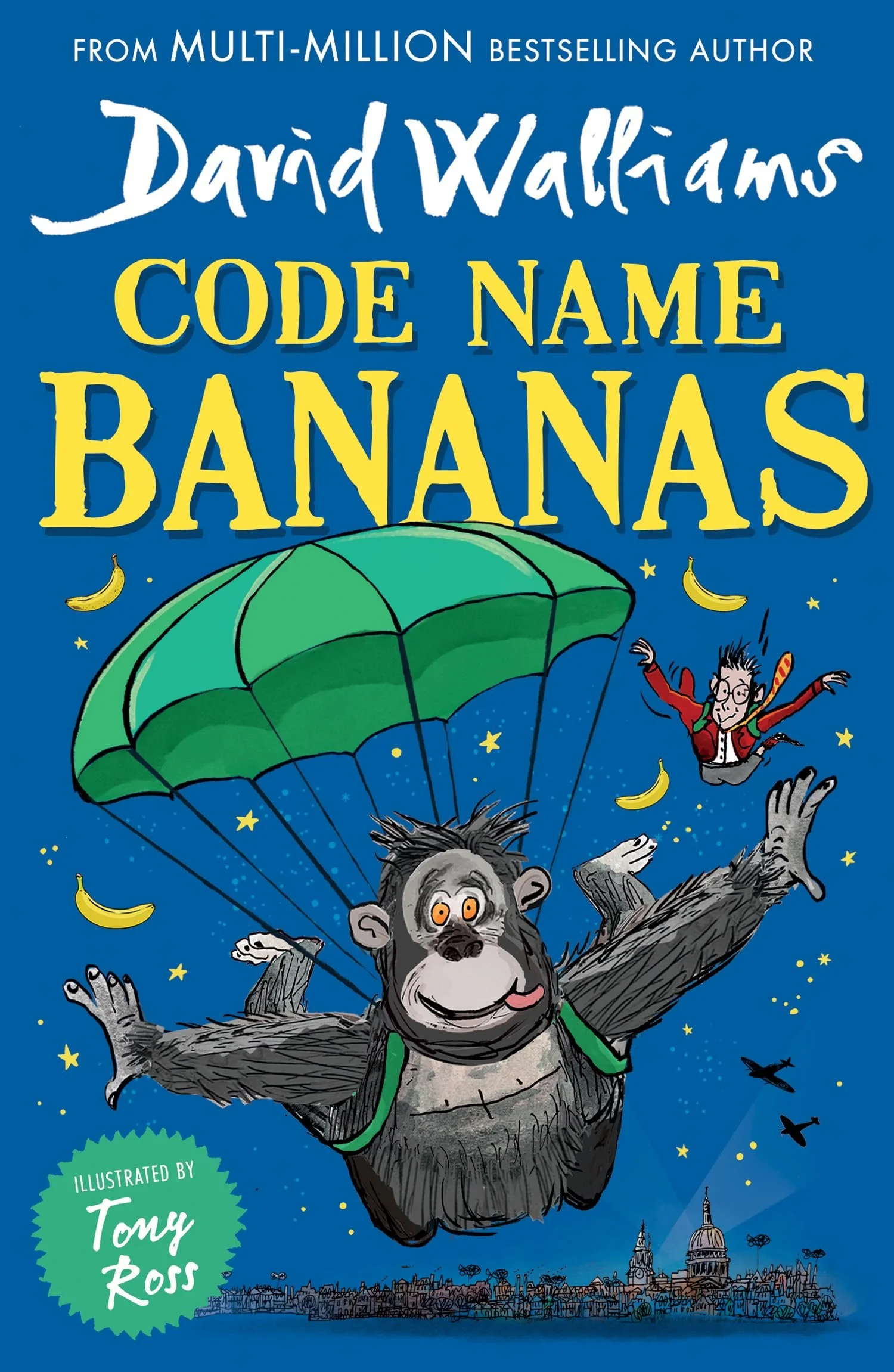

Because I came to the book as an adult reader, I was very aware of the typography. Walliams and his designer clearly aim to make the page itself feel like part of the performance: giant sound-effect words, wild changes of font, bangs and crashes that curve across the spread. I’ll be honest: I found it a bit distracting at times. My eyes wanted the story to flow, and the different fonts sometimes felt like being poked in the ribs. But I can absolutely see the appeal for its core audience. Those choices keep less-confident readers engaged; they make the Blitz feel visceral without resorting to graphic description; and they invite children to hear the book in their heads, not just see it. The text is also supported by Tony Ross’s illustrations, which are lively, slightly anarchic and perfectly matched to Walliams’s jokes.

In terms of Walliams’s style, this book is very much in line with the rest of his work: big comic set-pieces, grotesque adults, the odd bodily-function joke, and a refusal to talk down to children about fear or sadness. There’s a scene where a simple “Goodnight” turns into a joke about Eric confusing who is who—

“Say goodnight, Eric,” he said. “Goodnight, Eric,” repeated the boy. “WAIT! I am Eric!”It’s a tiny moment, but it shows his knack for turning basic wordplay into something kids will want to read aloud. Underneath that silliness, he is quite deliberate about threading in themes of loyalty, bravery, and standing up to bullies in all their shapes.

What interested me most, as an adult reader, was how the book handles war for young readers. Stories set in the Second World War often go for trauma, earnestness and obvious moral lessons. Code Name Bananas does something different. It keeps the danger present—bombs, air raids, the threat to the zoo animals, the looming Nazi plot—but the tone stays adventurous and comic. Walliams trusts children to cope with the idea that the world can be genuinely dangerous, while also giving them a gorilla in a disguise to laugh about.

That tension between darkness and daftness is where the book is most interesting to me. On one page, you have real historical figures like Winston Churchill and the reality of Nazi Germany; on the next, you might have Gertrude doing something utterly ridiculous to save the day. For a child, that blend might offer a way into learning about the war that is emotionally manageable: the facts are there, but wrapped in fun. For an adult, there’s a bit of whiplash, but also a reminder that children don’t experience “serious” topics in the same rhythm we do.

I do think the book is aimed first and foremost at young readers, exactly as I’d categorise it: a children’s book mainly for children, with some bonuses for any adult reading along. The pacing, the humour, the visual layout and the clear moral lines all point to roughly 8- to 11-year-olds who are ready for a longer, more complex story but still enjoy lots of pictures and visual play on the page. I consider it a good fit for readers who like animals, adventure, and a bit of history.

Would I recommend it? Yes, with a small framing note. If you’re an adult reading Code Name Bananas on your own, as I did, it’s worth remembering that you’re stepping into a space built very specifically for children’s eyes and ears. The fonts that feel intrusive to me may feel exciting and empowering to a nine-year-old who isn’t yet convinced that reading is fun. The jokes that make me roll my eyes may be precisely the ones that make a child burst out laughing and ask for “just one more chapter”. In that sense, the book succeeds on its own terms: it aims to be a “whizz-bang epic adventure” about a boy and a gorilla that “might just save the day”, and it absolutely delivers that.

For children who already enjoy Walliams, or who love animals and slightly over-the-top adventures, this will probably be an easy hit. For adults curious about his style, as I was, Code Name Bananas offers a clear snapshot: big-hearted, noisy, visually playful, and unafraid to mix slapstick with sincerity. It’s not subtle, but it isn’t trying to be. It wants to make kids laugh, keep them turning pages, and smuggle in a few thoughts about bravery, friendship, and not letting bullies win.

What stays with me is less the plot mechanics of the Nazi scheme and more the image of a boy who finds comfort at the zoo when the world is literally exploding around him. That feels like a very recognisable impulse: when everything is frightening, you go to the place where you feel known, even if that place is a gorilla’s enclosure. The book suggests that courage doesn’t start with grand speeches; it starts with protecting the thing or person you love, even when you’re scared.

So yes, I recommend Code Name Bananas—especially to young readers, or to anyone sharing bedtime stories with children who like their history with a hefty side of havoc. And it leaves me with a small question I’ll pass on to you: when you imagine sharing wartime stories with children, do you lean towards realism and restraint, or are you happy to let a big, banana-loving gorilla crash through the narrative and make them laugh as they learn?