Starting 2026 with an English Literature Degree

In case of TLDR:

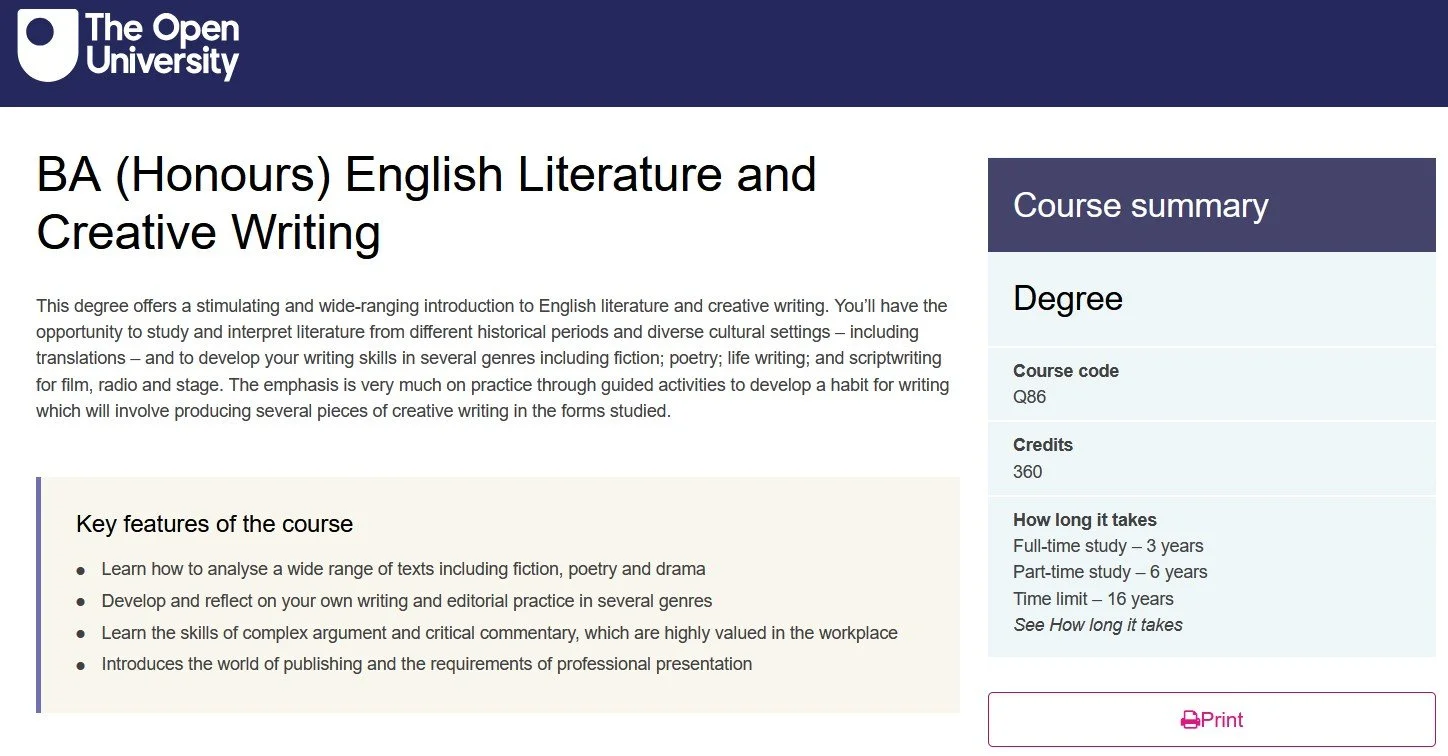

In a world where AI can summarise any book in seconds, I’m not studying English literature to get more information—I’m doing it to train my attention, my taste, and my voice. Most of all, I do it out of love for reading. I want to read slowly and deeply, to sit with difficult texts instead of skimming everything, and to learn how great writers build sentences that stay with you long after the page is turned. A degree gives me structure, discipline, and real feedback—things I can’t get from casual self-study or clever tools alone. It’s my way of choosing depth over shortcuts, and of making sure that, in a time when almost anything can be generated, my thinking and writing still feel unmistakably my own.This is the degree I committed myself to: BA (Honours) English Literature and Creative Writing.

Why do such a thing in the age of AI, where everything—almost everything—can be searched and freely available? This is my reflection.

I’m doing an English literature degree now because I live in the age of AI, not despite it. AI can summarise novels for me in seconds, but AI can’t replace what happens when I sit with a book, wrestle with a paragraph, and slowly change my mind about something.

I don’t want my reading life to be only skims, snippets, and summaries. And I’m glad it has not been like that even now. I want to train myself to stay with difficult texts, to understand nuance, to notice patterns, and to hold multiple interpretations at once. A degree forces me into that kind of deep, deliberate reading in a way casual reading never quite does.

AI can generate a passable paragraph on almost anything. That’s precisely why I want my own voice to be unmistakable.

Studying literature and creative writing gives me a structured way to understand how great writers build rhythm, meaning, and emotional power—and then to practice doing it myself. I’d like to believe that I’ve been doing so in my 25 years of writing, but I want to be better AND sure about that. I don’t just want to consume language; I want to shape it. This degree is one way of saying: my words matter enough to train them properly.

I yearn for structure, rigour, and feedback I can’t get from self-study. Yes, I could read all the texts on my own and Google the information for free. But I know myself: without a framework, everything competes with everything else in my life. I’m not so worried about the lack of discipline, but I am worried about trying to do too much and losing focus. The degree gives me:

A curated path instead of a random pile of books.

Deadlines and discipline that protect reading and writing time.

Feedback from tutors and peers who are not my friends, not my blog readers, and not an algorithm.

That rigour creates a different kind of growth—less “nice ideas in a notebook,” more “I have to make this essay actually work.”

What I really want isn’t just to “have read” certain books; I want to be in conversation with them—a long conversation with ideas. An English lit degree is a formal way of stepping into a centuries-long discussion about stories, power, language, identity, and what it means to be human.

In an AI world where answers can be spat out instantly, I want to learn how to ask better questions. Literature is one of the best training grounds for that: it refuses easy answers and rewards people who are willing to sit in ambiguity (and I love sitting in ambiguity—it’s an occupational hazard).

Speaking of occupation, I’m not doing this degree in a vacuum. It connects directly to things I already care about and do: my book blog and future writing projects; my professional life, where understanding narrative, perspective, and language helps me as a communicator, analyst, and facilitator.

The degree isn’t just “for fun” or “for a job.” It’s a way of aligning who I already am—a reader, a thinker, a writer-in-progress—with something formal, demanding, and recognised.

So, in circling back to why do such a thing (the English Lit degree) in the age of AI, there’s something radical about committing to serious reading and writing when algorithms can do the surface-level work for me. It’s a way of saying:

I’m not outsourcing my curiosity. I’m not outsourcing my taste. I’m not outsourcing my thinking.

Studying literature is one way I protect and deepen my humanity. Lastly, I know that if I don’t do this, I’d regret it on my deathbed.