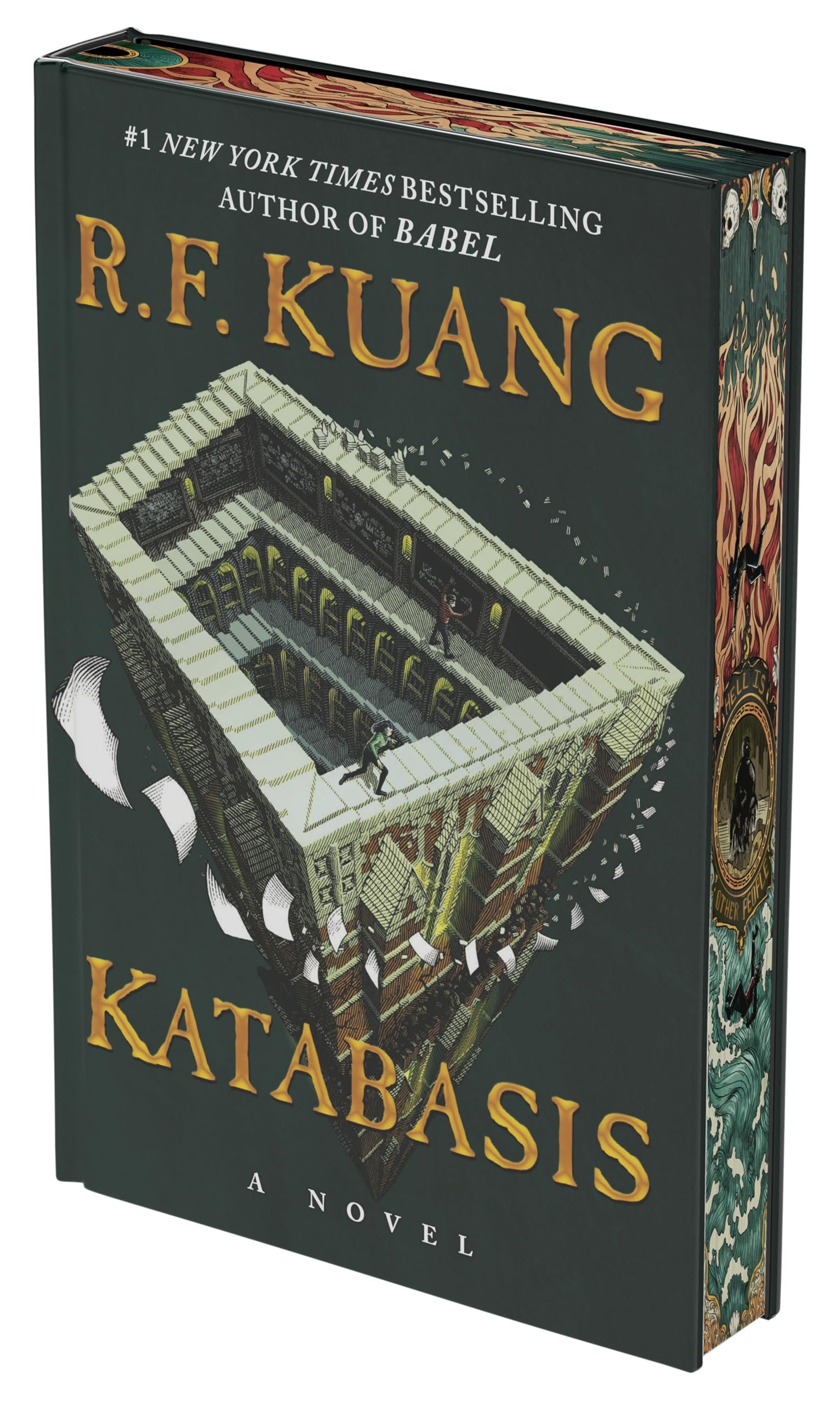

Katabasis

I own a copy of this deluxe limited edition and the standard paperback with the same cover.

I went into R.F. Kuang’s Katabasis already half in love with the idea: a dark academia fantasy where two Cambridge PhD students trek through Hell to rescue their dead supervisor, with logic and philosophy baked into the magic system.

I picked it up because I’m persistently fascinated by underworld journeys and because I wanted to see philosophy and logic threaded through an actual story rather than fenced off in a textbook. The book absolutely scratched that itch for me, marrying an old story pattern with very modern questions about proof, truth and who gets to succeed in academia. And yes: I recommend it.

The premise is delightfully blunt. Alice Law, a Cambridge postgraduate in analytic magick, has accidentally killed her supervisor, Professor Jacob Grimes, in a magical accident that sends his soul straight to Hell. Without him, she has no thesis chair, no recommendation letter, and no future in the field she has sacrificed everything for. So, as the book’s opening chapter lays out, “Alice Law set out to rescue her advisor’s soul from the Eight Courts of Hell.”

That straightforward sentence hides how much is at stake: guilt, ambition, and the terror that you might have ruined your one shot at the life you’ve built your entire identity around. The descent is a quest, but it’s also a job-security crisis in robes and chalk dust.

Alice, as a protagonist, is catnip if you’re interested in how people live inside systems of proof and performance. She’s brilliant, obsessive, and deeply invested in being the cleverest person in the room. Before Grimes’s death, she had already whittled her life down to research, teaching, and the desperate pursuit of approval from a man the field has decided is a genius. After the accident, that intensity tips into something darker: a mix of survivor’s guilt, rage, and the sense that the only way to atone is to fix the problem herself, no matter the cost. It feels both shocking and grimly plausible that she’d bargain away half her remaining lifespan for passage to Hell for her CV.

Opposite Alice, we get Peter Murdoch, her academic rival and unwanted companion on the journey. On paper, he is the golden boy: charismatic, effortlessly likeable, a favourite of the department, the sort of student who seems to glide where Alice grinds. In a field that still runs heavily on patronage and personal charm, Peter is the person the system was built to reward. But Kuang is more interested in the cracks. Peter is just as bound to Grimes as Alice is, in different ways; his confidence has been trained to fit a particular mould, and his complicity in that system becomes one of the book’s most devastating reveals. What begins as a spatty rivalry slowly becomes a study in how two people can be trapped by the same structure, even as it appears to favour one over the other.

One of the joys of Katabasis for me is that the magic is built out of logic. Analytic magick here runs on proofs, paradoxes and formal systems, the way other fantasies run on bloodlines and prophecies. Kuang uses classic puzzles such as the Sorites paradox, the Liar paradox, and the Hangman paradox to both world-build and develop character. This lets us see how Alice and Peter think, not just what they feel.

There’s a line early on that captures this rigorous mindset—this is Alice in Chapter One:

She checked and double-checked her chalk inscriptions. She always left the closing of the circle to the end, when she was absolutely sure that uttering, and thereby activating, the pentagram wouldn't kill her. One always had to be sure. Magick demanded precision. [...] She gripped her chalk. One smooth stroke and the pentagram was finished.I loved watching that demand for precision play out in action: how they set up circles, hedge bets with carefully phrased bargains, and use logic as both toolkit and shield. It felt like watching a philosophy seminar where the wrong inference could get you disembowelled.

Hell itself is built out of books as much as it is built out of fire. Kuang’s underworld is the Chinese Eight Courts of Hell by way of Plato, Dante, T.S. Eliot, Orpheus and Aeneas; the novel opens with an epigraph from Phaedo, and we’re told Alice, since Professor Grimes's demise, “had spent her every waking moment reading every monograph, paper and shred of correspondence she could find on the journey to Hell and back.” She’s parsing The Divine Comedy, The Waste Land and classical myths as if they were field reports rather than literature.

The result is that Hell feels textual: a place mediated by reading, translation and debate. For a reader like me, who enjoys watching stories talk to other stories, this was delicious. You can feel Kuang asking what happens when our map of the afterlife is itself a collage of other people’s metaphors and grudges.

All these might sound very cerebral, but the book keeps returning to a simple, resonant question: what counts as proof? Alice and Peter trust logical proof almost more than they trust other people. If something can be formalised, written down, pared into premises and conclusions, then it feels safe and real. But Hell keeps pushing them into situations where logic is necessary but not sufficient. Contradictions can be literally weaponised, with an object called the Dialetheia making mutually exclusive truths stand side by side.

For me, that ran in parallel with the academic question of proof: how do you prove you’re worthy, original, and brilliant when the metrics are skewed, and the judges are compromised? Because this is very much dark academia. The 1980s Cambridge setting gives us fog, cold libraries, and college formality, but the real darkness lies within the institution itself. Kuang is upfront about the mental health toll, the burnout, the way students crave validation from superiors who may be actively harming them. The dark side of academia can still be adored and defended by the structures that depend on its prestige.

Alice’s determination to drag Grimes back is complicated by the fact that he has harmed her; the novel is interested in that knot of love, ambition and trauma, and in the horror of realising that your own brilliance has been used against you.

Emotionally, I read Katabasis in a very specific mood: I wanted philosophy in motion. I wanted logic and paradox not just explained, but dramatised, and I got that. The long conversations about proof and truth made me feel seen as a reader who actually enjoys a bit of intellectual scaffolding with her fantasy. I can see why some critics have called the book “bloated” or accused it of getting tangled in its own cleverness, particularly in the more introspective sections; if you’re impatient with theory, the pacing may feel dense. But for me, that density was part of the appeal. I liked that Hell isn’t just a gauntlet of monsters; it’s a gauntlet of ideas.

As a dark academia fantasy, it sits in conversation with books like Kuang’s Babel, Donna Tartt’s The Secret History, Naomi Novik’s Scholomance trilogy, and other campus fantasies that take the university seriously as both a place of learning and a machine that eats its young. Where Katabasis feels distinct is in just how “philosophy-adjacent” it is. Instead of vague references to knowledge and transgression, it gives you actual logical puzzles, metaphysical debates, and a very literalised version of “publish or perish”. It’s also, importantly, an adult novel; the emotional terrain is heavy (abuse, self-destruction, suicidal ideation, the ethics of complicity), even when the banter between Alice and Peter keeps it readable.

So who is this for? I’d recommend Katabasis to readers who like their fantasy formally clever and emotionally raw: people who enjoy logic puzzles, underworld myths, mentorship stories gone wrong, and campus fiction that doesn’t romanticise the grind. If you want a fast romp, this probably isn’t your book. If you’re curious about how fiction can use philosophy without becoming a lecture, then it very much is.

In the end, what stayed with me wasn’t just the architecture of Kuang’s Hell, or the satisfying clockwork of the magic system, but the way she asks what we are willing to sacrifice for the lives we’ve convinced ourselves we deserve. When your whole existence is structured around being provably right, what does it mean to walk into a place designed to undo your certainty? That’s the question I carried with me after closing the book.

If you’ve read Katabasis, I’m curious: which part of the descent felt truest to your own idea of Hell – the courts, the paradoxes, or the academic politics?

P/S: I’m excited that Katabasis is in the works as an Amazon TV series from writer Angela Kang!